Envy is undoubtedly one of the most painful emotions. At its core, lies a distressing and isolating feeling of burning shame when we are seen by another to be envious; 'caught in the act' of feeling something taboo, prohibited. Envy is arguably even less acceptable in society than jealousy. When we are jealous we are afraid that we might lose what we have; that we might for example lose a partner to someone who we perceive to be better looking or more interesting than we are. Jealousy is a response to the threat of loss of someone we love. Envy is a response against annihilation of the self, hence its links with shame. We could say that like envy, jealousy isn't generally perceived to be an emotion welcomed with empathy and understanding at first, yet somehow there is a societal perception that it is more reasonable to guard something that you have, rather than covet something you don't.

“‘Envy is the angry feeling that another person posseses and enjoys something desirable - the envious impulse to take away or spoil it. ‘ ”

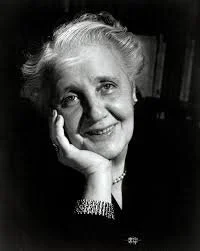

Melanie Klein

Perhaps it is the spoiling nature of envy that Klein illustrates which makes it so taboo.We don't want to spoil anyone else's fun; rain on their parade. Or at least we feel we shouldn't. But with envy, not only do we want what the other person has, we crave the pleasure of their misfortune, commonly known as 'schadenfreude'. Although levels of envy and associated 'schadenfreude' sit on a continuum, there is no escape from the fact that envy is one of the seven deadly sins, perhaps the deadliest, because at its worst it can be downright malevolent.

“‘I would even suggest that it is unconsciously felt to be the greatest sin of all, because it spoils and harms the good object which is the source of life.’ ”

For Klein, our relationship with envy is developmental and the result of our earliest object relations: Envy and aggressive instincts have a 'constitutional' basis, combined with a range of interdependent factors concerning pre and post natal relations. Envious feelings are the outcome of our split relationship to the breasts, which give nourishment, yet cruelly take it away. As a means of coping with the anxiety provoking and persecutory nature of this dynamic, the child splits the breasts into good and bad 'part objects': the ‘paranoid-schizoid’ position.

The child may feel destructive urges towards the 'bad' breast because it feels it is 'mean and grudging' (Klein, 1977, p.183), or the 'good' as its gift of milk 'seems something unattainable' to the infant (ibid.) Whether or not we agree with Klein's etiological definition of envy, - which I feel is too focused on constitutional factors, more on this later- it nonetheless illustrates the primitive feelings of impotent rage we experience when we don't get what we want, or miss out on the praise we deem to be rightfully ours.

In the midst of envy, when we see the success of other people on social media, instead of wishing to share in their celebrations and wishing them well, we experience the destructive urge to spoil. This leads to guilt and self punishment: we then cannot accept care or encouragement from others, either because we unconsciously feel that they may be secretly envious of us, or because our own envy has made us bad inside. We cannot take anything in that is good for we fear that it will be spoilt because our internal envy is so powerful that it devours and annihilates everything it comes into contact with.

Envy has its association with 'cupiditas', an avaricious longing that also may wish to spoil or destroy another person's good fortunes.This coveting dynamic is archetypal and appears across mythology. In Tolkien's 'Lord of the rings' Gollum greedily covets his 'precious' ring which he perceives to have been unjustly stolen from him, despite originally having obtained it through murder. The 'precious' Ring is talismanically imbued with magic powers which render its bearer omnipotent enough to disappear at opportune moments, as if in a waking lucid dream. Frodo is sent on a virtuous hero's journey by Gandalf to destroy the ring and avert its exploitation by evil, yet this noble act is almost jeopardised; not only by Gollum's pursuit, but also by Frodo's own growing sickly greed to harness its power for his own ends. Frodo now wishes to use the ring to enjoy omnipotent feelings of transgression, perhaps fuelled by Gandalf's strict Grandfatherly prohibitions at the outset of his journey.

The ring becomes increasingly heavy as Frodo's journey goes on, as if he is not only paying the price for his transgressions, but is also weakening by the second as a result of the envious attacks of his pursuer which now drain his already dwindling resources. At the apex of Frodo's descent into near oblivion, he seems to identify with and take on the characteristics of Gollum: his greed to keep the ring for himself and use its power seem much more akin to what we associate with Gollum's behaviour than Frodo's.

Envy itself is greedy because it is insatiable, fuelled by masochistic feelings of shame. Instead of 'the ring' in Tolkien’s work, our eyes devour the new electronic talisman of Instagram. Envy has its arcane, archetypal associations with the 'evil eye' and for millennia we have 'eyed up' the achievements and the perceived blissful happiness of others, subsequently plunging into bouts of guilt and shame as we feel that we have somehow exploited or wanted to 'scoop out' (Klein, 1977, p.183) all that is good from the other so that they feel as devalued as we do. We also feel that now we can own what the object of our envy has and need not be envious anymore. Of course that's a painfully obvious illusion.

“Greed is an impetuous and insatiable craving, exceeding what the subject needs and what the object is able and willing to give.”

The unequal nature of society itself has nurtured greed and envy with rapacious capitalism and many people and the planet itself are now suffering the consequences. And this is where the Kleinian perspective shows its limitations; not only because of the lack of emphasis on subsequent object relations and the environmental elements which Fairbairn, Winnicott and Bowlby certainly went some way to address, but also the enormous cultural and societal factors at play. Society exacerbates and compounds these early Kleinian dynamics. At school we quickly realise that there are others that are 'better' or 'more gifted' than us at certain things, which means that without the right level of care and attention, we are vulnerable to internalising the idea that we are ‘born with’ apriori attributes which are good or bad: in this sense we are in danger of becoming binary or fragmented 'part objects' and seeing others in the same way.

If we are fortunate, we have benefited from parents/ caregivers who have managed to communicate that failures are not the end of the world, (even if they feel like it at the time) and we can grow and learn from them. Yet if they themselves have unresolved narcissistic wounds too deep to bear, their children can soon feel that they are defined by their successes and failures rather than loved as a person (a ‘whole object’ in Kleinian terms). As Winnicott highlighted, this leads people to turn away from their true selves and they become condemned to formulate false personas to meet the needs of the projected other for the rest of their lives. As they have felt turned away from by others, they turn away from themselves. These false selves are projected across social media with these now famously 'curated' posts which stoke up the culture of envy built on 'likes.' I cannot overemphasise here in this context of envy how terribly inequitable society is itself: some people do have more than others and get better and bigger breaks in life. It's not always about our constitutional death drive or malfunctioning relationship with the breast! People are passed over and traumatised because of race, class or gender among a wide range of other socio-political factors. In this sense envy is the most legitimate and understandable emotion of them all and therefore warrants the most empathy both culturally and interpersonally.

Acutely persecutory feelings of shame and guilt can be worked through in psychotherapy. This enables us to integrate these parts of the self that we have deemed to have been hitherto unacceptable to think about despite the fact they have often been acted out and so painfully felt. It can be particularly hard to think about our own aggression and envy, but the capacity to do so enables us to reflect upon the projection of our inner worlds and external reality: what is my fantasy about this situation? What really happened there? Of course we can never really know completely what is what in every situation (this would be delusional idealism which in itself is persecutory), but it at least becomes less painful to think about it.

As we are able to express our rage, envy, sadness and guilt we can then begin to take in some good and experience some feelings of love for ourselves and give it to other people. This also leads to feelings of gratitude. Importantly, gratitude cannot be experienced by telling ourselves or other people to be grateful for what they have and to stop thinking about what they don't. This is deeply unempathic, unforgiving and only leads to a gratitude based on guilt. Those of us who have experienced relational or narcissistic trauma will be particularly susceptible to this i.e. 'I should be grateful for all you have done for me and the great sacrifices you have made.' This is also why I am very wary of the idea of making a list of 'ten reasons why I should be grateful' despite the benign intentions that are perhaps behind it. As Klein affirmed, feelings of guilt are always there to some degree when we experience gratitude, yet this guilt is based on vulnerability and concern rather than self punishment. Love and gratitude can only be attained through grieving and experiencing a capacity for concern for the parts of ourselves and others we deem to have hurt or damaged. This process honours the depth and complexity of human experience.

Klein, M. (1977) Envy & Gratitude. London: Vintage.